Over two decades, the People’s Liberation Army Air Force has changed how it builds and uses airpower. PLAAF modernization moved from large numbers to advanced systems, widened long-range and maritime roles, and brought far better ISR and electronic warfare support online. A new National Defense University (NDU) study revisits the earlier “right-size” question and explains how China combined higher budgets with a more mature aerospace base to avoid several expected trade-offs.

Key facts at a glance

• Personnel levels today look similar to 2007, yet the combat fleet is smaller and far more capable. Fourth-generation J-10 and J-11 families dominate, and the J-20 adds a stealth edge. [1]

• Bomber totals are steady (~219), yet the H-6 series gained range, refueling, and standoff weapons; the H-20 is in development. [2]

• Support aircraft sit near 17% of the fleet versus about 31% for the U.S. Air Force, which still caps sustained reach. [2]

From quantity to quality: what changed since 2007

Since 2007, PLAAF modernization followed three clear lines. First, older J-6/7/8 and Q-5 types retired, while J-10 and J-11 variants took over; eventually, the J-20 entered serial production. Second, bomber numbers stayed flat but gained real punch through refueling and long-range weapons. Third, enablers—tankers, transports, AEW, and ISR/EW—moved from trial use to routine duty on longer patrols. [1] [3]

The path was not smooth. During the early 2010s, retirements outpaced new deliveries and total combat aircraft dipped. Even so, capability rose. By the mid-2020s, stealth, modern sensors, and networked weapons lifted combat power despite fewer aircraft on the ramp. [2]

Bombers, tankers and ISR: the backbone of reach

Long-range strike now sits at the center of PLAAF modernization. H-6K/N bombers, backed by refueling and standoff weapons, support anti-access/area denial plans against carriers and land bases. As the H-20 advances, the bomber force will likely add a deeper conventional and nuclear role, which in turn complicates allied planning cycles. [1]

Enablers also matter. The YY-20A tanker and Y-20 transport fleets extend range; meanwhile, AEW platforms stitch together strike packages and air defense. Nevertheless, the share of support aircraft still trails Western practice, so sustained operations far from China’s coast remain harder. [2] [3]

Force structure and command reform: a more joint PLAAF

China’s 2015–2016 reforms pushed tactical aviation to theater commands, while PLAAF headquarters kept bombers, transports, and airborne troops. Then, in 2023, most land-based PLA Navy aviation shifted under the PLAAF, which unified coastal air defense and maritime strike. Consequently, one service now runs both territorial and maritime air missions, and regular long-range patrols over the South and East China Seas have become standard. [4]

Industry, engines and procurement: domestic over import

The NDU update argues that PLAAF modernization avoided several assumed compromises. Rather than choose between small Russian buys and lower-end domestic designs, China combined limited imports with steady gains in the J-10/J-11 families and the J-20. At the same time, propulsion and air-defense advances (for example, HQ-9 series) cut reliance on Russian suppliers. Because budgets grew and supply chains matured, the PLAAF could add high-end systems without shrinking the force. [1]

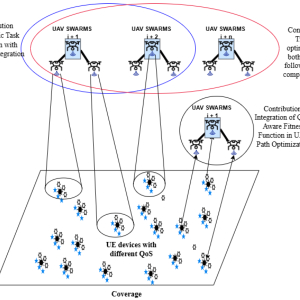

Uncrewed systems and teaming: from ISR to strike

China fields HALE WZ-7 and MALE BZK-005 drones, GJ-series UCAVs, and ISR/EW variants. Trials in crewed–uncrewed teaming mirror allied trends. As a result, persistent ISR and electronic attack at range now reinforce strike packages and raise the cost of counter-A2/AD operations. [1]

Strategic takeaways: a smaller fleet, a bigger problem

For U.S. and allied planners, the modern PLAAF no longer resembles a defensive, outdated air arm. Instead, it fields credible long-range strike, maritime interdiction, and dense ISR/EW support. The main shortfall is still enablers. Unless China lifts tanker, transport, and AEW/ISR numbers, power projection will remain short, sharp, and local. If Beijing closes that gap—especially while adding the H-20 and next-gen fighters—the balance of advantage in Western Pacific air operations could narrow further. [1] [3]

Method note: why this update matters

The authors reuse a simple frame—roles and missions, foreign versus domestic sourcing, high-tech versus low-tech, and combat versus support aircraft. However, they treat budgets, industry capacity, and the threat picture as separate drivers. That approach gives a more realistic view of PLAAF modernization and hints that rising strategic risk could push near-term choices toward more attritable drones alongside premium stealth platforms. [1]

What to watch in 2025–2030

• Pace of H-20 testing and its fit with nuclear and conventional strike roles.

• Growth of YY-20A, AEW, and ISR/EW relative to fighters—key for expeditionary reach.

• Operational use of crewed–uncrewed teaming in maritime strike packages.

• Industry progress on engines and sensor fusion for sixth-generation systems.

Internal link

For a wider view of enabling technologies, see our deep-tech airpower analysis: Wave of Transformative Deep-Tech Trends.

References

[1] Lauren Edson & Phillip C. Saunders, “Rightsizing the PLA Air Force: Revisiting an Analytic Framework,” NDU Press / Joint Force Quarterly 118 (July 15, 2025). NDU Press article page — Digital Commons entry.

[2] “China builds smaller but more capable air force,” Defence Blog (Aug. 25, 2025). Article.

[3] U.S. Department of Defense, Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2024 (Dec. 18, 2024). PDF.

[4] Army University Press, “Xi Jinping’s PLA Reforms and Redefining ‘Active Defense,’” Military Review (Sep–Oct 2023). Article.