In the halls of today’s major defence exhibitions, the changing face of defence branding has little to do with camouflage paint or turbine blades. The most aggressive new entrants present themselves less like legacy prime contractors and more like venture-backed software firms. Walk past the stands of companies such as Anduril, Shield AI or Saronic and the cues feel familiar from the tech world: dark interfaces, monospaced typography, product screens instead of hardware cutaways, and a tone of voice borrowed from developer culture rather than procurement manuals.

This is not simply a cosmetic update. The changing face of defence branding reflects a deeper shift in how capability is conceived, delivered and sustained. These firms are deliberately positioning themselves as software companies that happen to solve defence problems, not defence contractors that occasionally write code. Hardware remains essential, but it is increasingly modular, networked and designed to evolve through continuous software releases and data-driven optimisation.

In this emerging model, value accrues less to the steel and more to the software layers, data pipelines and connectivity that keep platforms tactically relevant. Analysts describe this as the “platformisation” of defence: a shift from one-off hardware programs to software-defined capability, where the decisive edge lies in the ability to iterate, integrate and scale at the pace of conflict.

Key Facts

From platforms to platforms-plus-code: Hardware still matters, but competitive advantage increasingly resides in software, data and connectivity rather than in the metal alone.

New founder and capital base: Defence-tech firms backed by venture capital are importing start-up culture, speed and risk appetite into an industry built on long cycles and risk aversion.

Dual-identity brands: New entrants must signal credibility to defence customers while remaining attractive to engineers, product managers and investors who expect a tech-company experience.

Brand as strategic infrastructure: The changing face of defence branding enables firms to recruit differently, partner differently and position themselves at the centre of dual-use technology ecosystems.

From Hardware Platforms to Software-Defined Capability

Historically, the organising logic of the defence industry was hardware-centric. Capability sat in ships, aircraft and vehicles delivered under large, tightly scoped contracts. Once commissioned, these systems moved into long and expensive sustainment cycles. Upgrades were measured in blocks or mid-life updates rather than continuous releases. Branding reflected that reality, with heavy iconography, metallic palettes and language focused on platforms, tonnage and firepower.

The software-first model inverts that logic. Today, the hardware is often designed as a relatively stable base, with open interfaces, modular payloads and generous size, weight and power margins. The real differentiation comes from the autonomy stack, the mission software and the data architecture that sits above it. As one senior executive recently put it, hardware is built once and made better every month because companies push new software across the fleet.

This philosophy also mirrors broader trends in software-defined warfare. Modern architectures must scale on demand, adapt quickly to new threats and support cheaper upgrades than traditional systems. Instead of treating each platform as a bespoke project, the goal is to field common digital backbones that can host multiple applications, sensors and effectors over time. In that world, the changing face of defence branding becomes the visible sign of software thinking applied to every layer of capability.

The Tech-Company Posture: Brand, Culture and Capital

When Aesthetics Signal Architecture

The visual language of the new entrants is not accidental. Black backgrounds, monospaced fonts, code snippets and product dashboards do more than look contemporary. They signal to customers and recruits that these businesses see themselves as builders of software-defined systems and developer ecosystems, not just airframes or hulls. In addition, taglines about autonomy at the edge and AI-driven decision advantage reinforce the idea that code, not steel, is now the primary lever of military effectiveness.

In recruitment terms, this shift matters. The same data scientists and machine-learning engineers who might once have joined fintech, cloud or gaming now see a familiar aesthetic and vocabulary at defence-tech firms. They recognise agile rituals, product roadmaps and DevSecOps practices. As a result, the changing face of defence branding lowers the psychological distance between defence and the rest of the high-growth tech ecosystem and makes it easier to attract scarce talent into national security problems.

Follow the Money

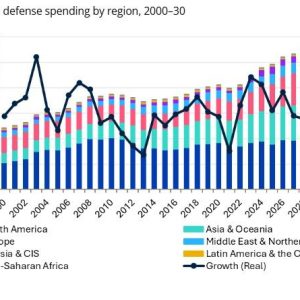

Capital also drives this shift. Over the past decade, venture investment in defence technology has grown by several hundred per cent, with 2024 and 2025 setting new records across NATO markets. Many investors who once avoided defence now view autonomy, sensing and resilient communications as critical infrastructure and long-term growth themes. The most prominent defence-tech unicorns now command multi-billion-dollar valuations and raise funding rounds that look similar to mainstream late-stage tech deals.

To access that capital, firms must present a growth story investors understand. They need scalable software margins, repeatable product lines and a credible route to global markets. This requirement, in turn, encourages subscription models, continuous-upgrade offerings and data-as-a-service layers that sit on top of conventional hardware sales. In many cases, visual identity, messaging and investor decks work together to place these companies inside the broader story of deep tech and dual-use innovation rather than as niche subcontractors.

Over time, a flywheel effect appears. The more a company behaves like a high-performance software firm, the more talent and capital it attracts. With each turn of that wheel, it can iterate product faster, close operational feedback loops and grow its developer ecosystem. In this way, the changing face of defence branding becomes both a cause and a consequence of the underlying business model.

Dual-Identity Brands: Between Command and Code

This new generation of firms now operates with a permanent dual identity. On one side of the house sit defence ministries, acquisition agencies and uniformed operators who prize reliability, compliance and sovereign assurance. On the other side are investors, engineers and product managers who expect experimentation, rapid iteration and a culture that tolerates constructive failure. Here, the brand becomes the bridge between these worlds, a common language that can speak mission assurance to one audience and shipping velocity to another.

However, that dual role carries real risk. If a company leans too far into tech-industry rhetoric, it may look unserious or naive to military customers who work in a world of high stakes and strict regulation. If it leans too far into traditional defence imagery, it risks losing the very talent and capital it needs to deliver software-defined capability at scale. The most credible players are therefore those whose changing face of defence branding is backed by visible substance: disciplined engineering, proven certification pathways and operational deployments, not just slick demos.

Authenticity as Licence to Operate

Consequently, authenticity is becoming the decisive test. A company cannot simply repaint its website in black and adopt a monospaced font, then claim the mantle of a software-native defence firm. Customers and engineers will quickly detect any gap between brand and behaviour. Authentic brands usually show a clear through-line: agile delivery contracts, regular software drops to the field, feedback channels from warfighters into product teams, and leadership that speaks fluently both in mission language and in code.

In that sense, the changing face of defence branding is not about appearing disruptive for its own sake. Instead, it signals that a company is genuinely organised to deliver continuous capability to the warfighter and to absorb operational lessons from Ukraine, the Red Sea and other live theatres. When story and substance stay aligned in this way, brand turns into a strategic asset rather than a thin marketing layer.

Implications for Defence Communications and Incumbents

This evolution also has important consequences for how the wider sector communicates. As we have argued in previous analysis of Europe’s rearmament and industrial readiness,[1] the most effective players combine credible hardware production with agile digital layers. The same pattern now applies to narrative. The strongest stories connect tangible platforms to the software, data and ecosystem effects that sit above them.

For established primes, the lesson is not to mimic the visual tropes of start-ups but to internalise the underlying logic. That means treating software as a first-class citizen in communications and elevating the engineering teams that build autonomy and battle-management tools. It also means being clearer about roadmaps and iteration cycles. In parallel, companies need to explain to governments how new commercial models — from continuous delivery to performance-based logistics driven by data — can coexist with legitimate concerns around assurance, safety and oversight.

For newer entrants, the challenge is endurance. Defence remains an industry where operational credibility is earned over years, not quarters. The companies that will shape the next decade will be those that align their venture-style pace with the mission realities of long campaigns, contested logistics and coalition interoperability. Their brands will have to speak not only to early adopters in special operations units, but also to the staff officers and acquisition officials who must knit new capabilities into doctrine and force structure.

Conclusion: Code as the New Corporate Colour

Seen from the outside, the black backgrounds and coding fonts that now dominate parts of the exhibition floor might look like a short-lived fashion statement. In truth, they mark the visible edge of a deeper transformation in how defence capability is built, funded and explained. The changing face of defence branding is inseparable from the rise of software-defined warfare and from the cultural shift taking place inside the companies that enable it.

As conflicts modernise, the firms most likely to thrive will be those that think and act like high-performance software companies while still meeting the exacting standards of the defence enterprise. They must move fast, adapt, iterate and remain accountable. In that sense, the future of defence communication will be written in code as much as in copy. The brands that endure will be those where the visual language of tech is matched by real, repeatable delivery for the warfighter.

References

- Defence Agenda, “Europe’s defence readiness against Russia”, available at: https://defenceagenda.com/europe-defence-readiness-against-russia/

- Bain & Company, “Defense Investment at a Turning Point”, 2025, available at: https://www.bain.com/insights/defense-investment-at-a-turning-point/

- McKinsey & Company, “European defense tech start-ups: In it for the long run?”, 2025, available at: https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/aerospace-and-defense/our-insights/european-defense-tech-start-ups-in-it-for-the-long-run

- Atlantic Council, “Commission on Software-Defined Warfare”, 2025, available at: https://www.atlanticcouncil.org/in-depth-research-reports/report/atlantic-council-commission-on-software-defined-warfare/

- Defence Connect, “From tanks to tech: The changing face of defence branding”, 2025, available at: https://www.defenceconnect.com.au/geopolitics-and-policy/17201-from-tanks-to-tech-the-changing-face-of-defence-branding

- Axios, “Defense tech giant Anduril now valued at over $30 billion”, 2025, available at: https://www.axios.com/2025/06/05/anduril-vc-funding

- Financial Times, “Silicon Valley defence start-up Shield AI hits $5bn valuation”, 2025, available at: https://www.ft.com/content/ba8d0057-7a5c-47d4-b0ce-b12617305340