What is actually getting cheaper—and why it matters

The headline drop in Shahed drone unit cost stems from three interlocking dynamics: localization, simplification, and scale. Localization replaced Iranian imports with Russian production at Alabuga, cutting logistics and markup. Simplification shaved non‑essential components—e.g., lighter airframes and engines configured without starters and flywheels—to reduce bill‑of‑materials and assembly time [5]. Scale then amplified both effects, driving a steeper learning curve and enabling bulk procurement of commodity electronics.

The cost story is strategic, not just tactical. At ~$70,000 per weapon—or even at the $20k–$50k band used by some analysts—the Shahed family creates a punishing exchange rate versus surface‑to‑air interceptors that can cost several hundred thousand dollars each. That asymmetry incentivizes saturation raids and complicates defender magazine depth, especially when attacks blend decoys, altitude stratification, and route diversity.

“Cheap, expendable mass is the point. If a drone priced like a pickup truck forces an interceptor priced like a sports car into the sky, the attacker banks the spread—and learns from every volley.”

The price curve: from imports to localized mass production

Early Russian procurement relied on Iranian supply chains. Open‑source reporting based on leaked documentation suggested Russia paid roughly $290k per unit on 2,000‑drone orders and ~$193k per unit for 6,000‑drone tranches in 2022 [1]. As the war lengthened, Moscow pivoted to licensed production and then to deeper localization. By mid‑2025, Ukrainian defense intelligence briefed that domestically produced Shahed‑type drones at Alabuga were approaching a Shahed drone unit cost of ~$70,000 [2].

Independent think‑tank work triangulates close by. CSIS analyses published in February and May 2025 estimate unit costs in the ~$20k–$50k range depending on avionics, warhead, and component quality [3]. Ukrainian analysts counter that the lower bound likely reflects minimal configurations or decoy variants; in operationally relevant mixes, they argue a $50k–$70k range is more realistic. Either way, Russia has driven the Shahed drone unit cost into a tier where mass employment is financially rational.

Alabuga’s industrial playbook: simplification, substitutes, scale

Simplification. Field recoveries show engines and subsystems configured without convenience parts, trading peacetime reliability for wartime throughput. A stripped‑down design reduces part counts, technician hours, and failure modes—key levers when producing thousands per month.

Substitute supply. Commodity GNSS modules, commercial‑grade microelectronics, and widely available composites can be sourced through complex gray‑market networks. Even with sanctions, dual‑use flows continue to seep in through intermediaries, enabling a steady bill‑of‑materials for a basic Shahed configuration.

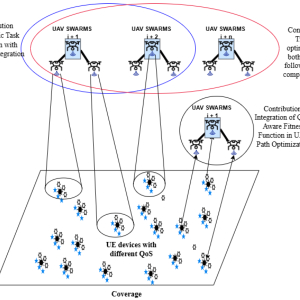

Scale and learning. Once assembly lines stabilize, cycle times fall and yields rise. In practice, that is how Russia can chase ambitions reportedly above 6,000 Shahed‑type units per month. At this tempo, a modest 5–10% unit‑cost reduction from learning effects quickly compounds over quarters.

The decoy question and mixed salvos

Another reason the cost picture matters: not every airframe in a salvo is a full‑fat loitering munition. Satellite imagery and OSINT reporting since 2024 highlight rapid construction of Shahed launch sites—with rails, storage, and technical zones—near Navlya (Bryansk) and Tsymbulova (Oryol), which support mixed packages of strike drones and decoys designed to stretch defenses [6]. In a mixed raid, a $10–$30k decoy that soaks up a $300k interceptor is a victory before the warhead‑bearing drones arrive.

Operational math: defenders pay the premium

From an air‑defense perspective, the economics are stark. Consider a simplified exchange:

Ukraine’s own long‑range industry responds by pushing the FP‑1—reported at ~$55k and ~100 units/day—aiming to mirror the attacker’s economics with attritable mass of its own [4]. Still, for NATO planners, the broader lesson is urgent: field layered counters (guns, EW, low‑cost interceptors) that collapse ρ toward parity while investing in hardening, dispersion, and rapid repair.

What to watch next

Quality vs. quantity. Lowering the Shahed drone unit cost invites reliability risks. The balance between simplified subsystems and mission success will shape sustainment demands and attrition in winter conditions.

Supply‑chain pressure points. Sanctions targeting bearings, engine components, MEMS IMUs, and RF front‑ends can raise unit costs at the margin. But expect rapid substitution unless interdiction is coupled with end‑user enforcement and customs analytics.

Counter‑UAS maturation. Expect accelerated procurement of programmable air‑burst munitions, 30–35 mm gun layers, and RF defeat. NATO allies should sandbox integrated kill‑chains where a $5k proximity‑fuzed round replaces a $300k interceptor for slow, low RCS targets.

Launch‑site agility. The build‑out of launch complexes in weeks, not months, implies a mobile, modular basing model. That increases the premium on ISR, strike reach, and time‑sensitive targeting against rails, storage, and crews.

Context & background reading

For a deeper strategic view on unmanned saturation and counter‑UAS trends, see our in‑house brief, Defence & Aerospace Strategic Trends.

References

- Leaked Iran–Russia pricing (2022) / localization plans. Washington Post investigation based on internal documents about Alabuga and a target of 6,000 drones. Inside the Russian effort to build 6,000 attack drones.

- Ukrainian intelligence via CNN: unit cost ≈$70k; output >6,000/month. (Secondary citations summarizing CNN brief.) RBC‑Ukraine; Economic Times.

- Shahed cost effectiveness and saturation employment. CSIS analyses: Calculating the Cost‑Effectiveness of Russia’s Drone Strikes; Drone Saturation: Russia’s Shahed Campaign.

- Ukraine FP‑1 program price/tempo. Associated Press: A Ukrainian startup develops long‑range drones and missiles.

- Design simplification/component sourcing in Shaheds. Conflict Armament Research field dispatches: Ukraine Dispatches (Issues 8–10) incl. Documenting the Domestic Russian Variant of the Shahed UAV.

- Launch sites at Navlya (Bryansk) and Tsimbulova (Oryol); rapid build‑out. Business Insider/Maxar OSINT: Satellite images uncover Russia’s exploding drone launch network.

- Primary article used for this rewrite. UAS VISION: From $300k to $70k: How Russia Mass‑Produced Cheaper Shahed Drones.

Further Reading

- Washington Post: How Iran enabled Russia’s Shahed production surge (May 29, 2025)

- ISW: Russian Offensive Campaign Assessment (Aug 7, 2025) — production tempo context

- NATO NCIA: C‑UAS Technical Interoperability Exercise (TIE24)

- US CRS (Congressional Research Service): Department of Defense Counter‑UAS (R48477, Mar 31, 2025)

- RUSI: Protecting the Force from Uncrewed Aerial Systems (2024)

- CSIS: Drone Saturation — Russia’s Shahed Campaign (2025)

- Institute for Science and International Security: Major Developments at Alabuga SEZ (Jul 28, 2025)