Russia has unveiled the Pantsir-SMD-E counter-drone air defence system at Dubai Airshow 2025. The new short-range design focuses on defeating unmanned aerial threats and precision weapons around high-value sites. In doing so, it departs from earlier mixed gun–missile Pantsir variants and moves to a missile-only layout.

Key facts

- Pantsir-SMD-E debuts as a short-range, export-focused counter-drone air defence system.

- The variant removes twin 30 mm guns and relies entirely on missiles.

- A new mini-missile, TKB-1055, is optimised for small unmanned aerial vehicles.

- The combat module can carry up to 48 mini-missiles or 12 full-sized interceptors.

- Modular architecture allows distributed launchers and sensors linked by fibre-optic networks.

- The system is designed for point defence of bases, refineries, airfields, and urban infrastructure.

From mixed armament to a missile-only counter-drone system

Earlier Pantsir variants combined medium-range missiles with twin 30 mm autocannons. That formula aimed to give batteries layered coverage against aircraft, cruise missiles, and close-in threats. However, recent conflicts have exposed the limits of gun-based close-in defence against small, slow drones.

Small quadcopters and loitering munitions present tiny radar signatures and unpredictable flight paths. As a result, 30 mm fire tends to waste ammunition while still allowing some drones to leak through. For Russia, this experience has pushed designers toward missile-heavy load-outs that offer better hit probability against small, agile targets.

Consequently, the Pantsir-SMD-E drops the guns entirely. The variant instead uses multiple layers of missiles, each tuned to specific engagement ranges and target sets. In practice, this change lets each launcher carry many more ready-to-fire interceptors within a similar physical footprint.

For operators, this evolution also simplifies training and logistics. Crews focus on missile employment, radar operation, and networked fire-control, rather than managing two very different weapon types on a single vehicle.

TKB-1055 mini-missiles and magazine depth

At the heart of the new design sits the TKB-1055 mini-missile. This compact interceptor is designed specifically for unmanned aerial vehicles and other small targets. According to Russian descriptions, it can engage drones out to roughly 7 kilometres and to altitudes near 5 kilometres.

The missile is smaller and lighter than the standard Pantsir interceptors. Therefore, a single combat module can mount up to 48 mini-missiles instead of 12 full-sized rounds. This increase in magazine depth is crucial when operators face dense drone activity or deliberate swarm tactics.

In many current conflicts, adversaries use cheap drones to exhaust air defence systems. They send repeated waves of unmanned platforms to force defenders to fire expensive interceptors. With a Pantsir-SMD-E battery, commanders at least gain more shots per launcher, which stretches limited stocks of missiles over longer periods.

Even so, the trade-off remains clear. Mini-missiles offer volume and responsiveness, but they have shorter range and smaller warheads than larger interceptors. As a result, the Pantsir-SMD-E must operate alongside other systems that handle higher-altitude threats and long-range cruise missiles.

Balancing reach, cost, and survivability

Modern short-range air defence design is an exercise in balancing reach, cost, and survivability. On one hand, a missile-only system like the Pantsir-SMD-E offers high accuracy and flexible engagement geometry. On the other hand, every missile shot still carries a significant financial cost, especially when used against very cheap drones.

Therefore, many armed forces are moving toward layered counter-drone concepts. They combine short-range missiles with jammers, directed-energy systems, and low-cost projectiles. The Pantsir-SMD-E counter-drone air defence system fits into that wider picture as the high-precision layer, responsible for protecting critical points when other measures fail.

Sensors and modular architecture

Pantsir-SMD-E also introduces an updated sensor and fire-control suite. The system combines a surveillance radar, a tracking radar, and an electro-optical sight. Together, these sensors aim to detect and track small unmanned aerial vehicles against ground clutter and in complex weather.

More importantly, the system adopts a modular architecture. Launcher modules, radar units, and command posts can connect through fibre-optic links. In turn, this layout lets operators separate sensors and shooters, which improves survivability and coverage.

For example, a radar head can sit on a hill or a tall building, while launchers remain hidden behind structures or earth berms. If an enemy attacks the radar, the missiles and crews remain intact. Conversely, if a launcher is hit, the sensor network can still support other nodes in the defended area.

This distributed approach also supports defence in depth around large facilities. Several launchers can protect different sectors of a refinery, air base, or command complex. Meanwhile, a central command post coordinates engagements and avoids fratricide.

Deployment options and urban defence

Russian officials have not detailed every chassis that will carry the Pantsir-SMD-E. Even so, the compact design suggests a wide set of deployment options. Launchers could sit on truck platforms, fixed foundations, or rooftop mounts in dense urban environments.

In cities, this flexibility matters. Critical infrastructure often lies close to civilian buildings and busy roads. Therefore, defenders need systems that can sit on small footprints and still provide overlapping fields of fire.

Pantsir-SMD-E’s modular layout is intended to support exactly that. Operators can scale the number of launchers and sensors to match the risk profile of each site. As a result, a single system family can protect both small forward operating bases and major strategic hubs.

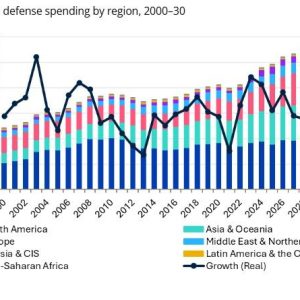

Context: drone warfare and regional demand

The debut of Pantsir-SMD-E comes as drone warfare reshapes almost every major conflict zone. In Ukraine, Syria, and North Africa, tactical units rely heavily on small unmanned systems for reconnaissance and strike missions. At the same time, state and non-state actors use one-way attack drones against refineries, ports, and airfields.

Consequently, demand for short-range air defence and dedicated counter-drone solutions has surged. Gulf states, North African countries, and Asian partners all face similar challenges around critical infrastructure. Dubai Airshow 2025 therefore provides an ideal platform for Russia to showcase a new counter-UAS product line.

However, Russia is not alone in this market. Western, Asian, and Middle Eastern suppliers are pushing their own layered systems that mix missiles, guns, jammers, and lasers. In this crowded field, the Pantsir-SMD-E counter-drone air defence system competes on magazine depth, modular deployment, and perceived combat experience from recent conflicts.

For potential buyers, the decision will hinge on more than brochure performance. Sustainment, training demands, and integration with existing command-and-control networks all play major roles. In addition, political and sanctions risk will shape how widely any Russian system can be adopted outside a limited circle of partners.

Implications for future short-range air defence

Pantsir-SMD-E illustrates several trends that are likely to define future SHORAD design. First, systems will carry more ready-to-fire interceptors to cope with drone swarms and saturation attacks. Second, modular layouts will spread sensors and shooters across wider areas to improve resilience.

Third, missile-only architectures will continue to appear, particularly where operators prioritise precision and controlled collateral effects. Yet gun-based and directed-energy layers will still matter, because they can offer lower cost per shot against basic drones. In practice, most modern air defence networks will mix these approaches rather than rely on a single concept.

Looking ahead, the key question is how quickly industry can reduce the cost of high-precision intercepts. If missiles, sensors, and controllers become cheaper and easier to maintain, systems like the Pantsir-SMD-E counter-drone air defence system will become more attractive. If not, operators may favour solutions that pair modest missile inventories with cheaper, high-volume effectors.

Either way, Dubai Airshow 2025 has underlined a simple reality. Any serious air defence portfolio now requires a dedicated counter-drone layer. Russia’s new system is one prominent answer to that requirement, and it will influence how other designers and customers frame their own next-generation SHORAD projects.

Further reading

- For comparative analysis of modern SHORAD and counter-drone architectures, see open-source studies by leading defence think tanks and industry reports.

- For a regional perspective on how Gulf states approach air and missile defence, review recent policy papers and air show briefings that focus on critical infrastructure protection.

- For context from Türkiye’s defence ecosystem, compare the Pantsir-SMD-E with indigenous short-range systems and integrated air defence programmes.