Military applications of synthetic biology are moving rapidly from theory to practice. Defence agencies now explore engineered organisms, DNA design and automated biofoundries to produce critical materials on demand. These advances promise more resilient logistics, faster medical responses and new types of protective equipment. At the same time, they raise serious dual-use concerns and global governance challenges.

Synthetic biology allows scientists to design and modify biological systems with increasing precision. Automated biomanufacturing facilities, often called biofoundries, use engineered microbes as “living factories” to produce fuels, polymers, fibres and even explosive precursors. In parallel, the tools to edit DNA and synthesise genomes are spreading worldwide. That combination creates both opportunity and risk for future military operations.

On-Demand Biomanufacturing and Military Logistics

One of the most prominent military applications of synthetic biology is battlefield biomanufacturing. Defence laboratories and industry partners are building biofoundries that use engineered microbes to “brew” critical materials. These facilities can ferment feedstocks such as sugar into high-performance cellulose for munitions, advanced polymers, lubricants or explosive precursors. In theory, this allows forces to shorten supply chains and produce key commodities closer to the point of need.

Pilot biofoundries already demonstrate how synthetic biology can support munitions production and energetic materials. Defence researchers use microbes to generate high-grade cellulose and other inputs for propellants and explosives. Looking ahead, deployable or modular biofabrication units could travel with forces into remote theatres. On isolated islands or austere bases, these systems might produce fuel, lubricants and repair materials on-site instead of relying on long, vulnerable supply lines.

If these concepts scale, military logistics could change significantly. Commanders would depend less on fuel convoys and resupply ships and more on local feedstocks for fermentation. Biofoundries would act as flexible “chemical plants in a container,” giving units some freedom from traditional logistics chokepoints. However, this model also ties biological production to energy, water and agricultural inputs, which must be secured and protected in any campaign plan.

For broader context on how advanced manufacturing is reshaping defence logistics, see our related analysis on additive manufacturing in military logistics .

Health, Protection and Bio-Based Countermeasures

Synthetic biology also accelerates medical and protective capabilities. Vaccine platforms based on mRNA and other synthetic biology techniques showed their value during the COVID-19 pandemic. Once scientists had the viral genome, they could design candidate vaccines within days. In a defence context, similar platforms could support rapid responses to natural outbreaks and engineered bio-threats.

Future forces may deploy compact biofabrication labs to generate vaccines, antibodies or other therapeutics close to the field. These labs could sequence an unknown pathogen, design a countermeasure and start producing doses far faster than traditional pharmaceutical pipelines. In principle, such systems improve resilience against both deliberate biological attacks and emerging diseases.

Synthetic biology also supports new classes of protective materials. Engineered organisms can produce novel fibres, coatings and sensors that enhance soldier protection or environmental monitoring. For example, bio-produced polymers may improve filtration in protective masks, while living biosensors could help detect hazardous agents at very low concentrations.

Dual-Use Risks and Synthetic Biology-Enabled Weapons

Despite these benefits, the military applications of synthetic biology come with profound dual-use risks. The same tools that help design vaccines and materials can also help design more dangerous biological agents. As DNA editing and synthesis technologies become more accessible, states and sophisticated non-state actors gain new options for biological attack.

By the 2030 timeframe, it may be technically feasible for well-resourced actors to engineer more contagious or virulent pathogens by combining known traits. Synthetic biology could enable organisms that bypass some existing detection systems or medical defences. It might also support attacks on agriculture, through pathogens that target specific crops, with major economic and food security impact. Ideas about targeting specific genetic traits remain largely theoretical, but they heighten concern about misuse of large genomic databases.

Synthetic biology also blurs the line between chemical and biological threats. A designer microbe could, in principle, biosynthesise a toxic chemical inside a water system or closed environment. Because the agent is generated in situ, it might evade traditional chemical detection architectures. This type of scenario highlights why biosecurity and chemical security can no longer be treated as entirely separate domains.

The convergence of AI with biotechnology amplifies these concerns. AI tools can help predict protein structures, propose gene edits and search for sequences with particular functional properties. Used responsibly, these tools accelerate drug discovery and vaccine design. Used irresponsibly, they could guide efforts to increase the stability, transmissibility or toxicity of harmful agents.

For a detailed discussion of these dual-use dynamics, see expert commentary from the Stimson Center on synthetic biology and security and threat assessments published by the U.S. intelligence community .

Governance Gaps: Biofoundries, DNA Synthesis and the BWC

Existing arms control instruments struggle to keep pace with these trends. The Biological Weapons Convention (BWC) bans the development, production and stockpiling of biological weapons. However, it lacks robust verification measures. At the same time, biofoundries, DNA synthesis services and cloud- based design tools make it easier to conduct advanced biology under a small physical footprint.

Without stronger transparency and oversight, it becomes harder to distinguish legitimate biodefence or medical research from prohibited offensive programmes. Commercial DNA synthesis firms already use screening protocols to flag suspicious orders. Yet these measures vary in depth and coverage, and there is no universal, binding standard for all providers.

As military applications of synthetic biology expand, states will need updated norms and possible confidence-building measures. Options under discussion include stronger information-sharing on high-risk experiments, more consistent screening for DNA orders and voluntary peer review for sensitive biodefence projects. None of these measures are simple, but the alternative is a widening gap between technological reality and legal frameworks.

Systemic Interdependencies and Biosecurity-by-Design

Synthetic biology sits at the intersection of health security, bioethics and defence policy. A breakthrough in DNA synthesis that reduces cost can speed up vaccine research. At the same time, it can lower barriers for harmful applications. Military adoption of bio-based products also depends on secure access to feedstocks such as sugars, nutrients and energy, which link biology to agriculture and energy infrastructure.

There is also a cyber dimension. Modern laboratories rely on networked instruments, cloud-based analysis and large genomic databases. These assets become targets for espionage or sabotage. An attacker could, in principle, corrupt DNA sequence files, interfere with design software or exfiltrate sensitive data on biodefence programmes. Consequently, biosecurity now spans from lab bench to battlefield to network, and defence organisations must treat biological data and lab control systems as part of their broader cyber threat surface.

For a wider look at how emerging technologies intersect with strategic stability, see our article on emerging technologies and strategic stability .

Strategic, Operational and Policy Implications

Strategic Implications

At the strategic level, military applications of synthetic biology could fuel a biotechnological arms race if norms and transparency do not keep pace. States that invest heavily in defensive biotech — such as vaccines, biosensors and rapid diagnostics — may gain resilience against a range of threats. Those that lag behind could feel more vulnerable to covert bio-attacks on populations, agriculture or deployed forces.

Strategists should integrate bio-attack scenarios more systematically into war games. These scenarios should cover not only pandemics but also targeted disruptions of supply chains, crops or troop health. At the diplomatic level, there is a window of opportunity to modernise BWC implementation, strengthen verification-adjacent practices and support global mechanisms for monitoring suspicious patterns in high-risk biological work.

Operational Implications

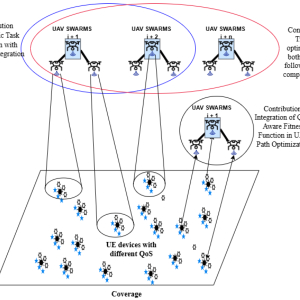

Operationally, embracing synthetic biology can make military forces more self-sufficient. Logistics units may eventually operate deployable biofoundries, and some personnel may need hybrid skills that combine engineering, biotechnology and maintenance. Doctrine for maintenance and repair might include bio-produced lubricants, fibres or coatings as standard options.

At the same time, force protection must expand to account for engineered bio threats. Units will require improved biological detection systems, tailored vaccination strategies and rapid-response biointelligence teams able to sequence unknown agents quickly. These capabilities should integrate with existing CBRN defence and with medical support structures.

Policy Implications

From a policy perspective, defence organisations need strong biosecurity and ethics oversight around synthetic biology programmes. This includes clear rules on who can access certain pathogen genomes, toxin- producing pathways or high-risk design tools. Personnel vetting and facility security must match the sensitivity of the work.

Investment in “dual-use literacy” is equally important. Decision-makers in defence need a realistic view of both the promise and the pitfalls of synthetic biology. They should avoid over-hyping quick technological fixes while also avoiding complacency about vulnerabilities. Internationally, allies may consider a more formal biosecurity information-sharing framework, analogous to existing arrangements in cyber defence.

Domestically, states will need to support a robust bio-industrial base. That means partnering with biotechnology firms, safeguarding supply chains for critical reagents and equipment, and ensuring that regulatory frameworks encourage responsible innovation. If done well, the armed forces can serve as a model for safe and ethical use of synthetic biology rather than a driver of new proliferation risks.

Conclusion: Harnessing Synthetic Biology Without Fueling Proliferation

Military applications of synthetic biology and biofoundries could transform how armed forces generate energy, materials and medical countermeasures. They offer powerful tools for more agile logistics and more resilient health protection. Yet these same tools, if misused, could enable new forms of biological and chemical harm.

The central challenge for defence planners and policy-makers is to harness synthetic biology responsibly. That means building strong biosecurity, investing in defensive capabilities, updating international norms and designing bio-enabled systems with safety and ethics in mind from the outset. The choices made in the coming decade will determine whether synthetic biology becomes a stabilising force for defence, or a new driver of proliferation and strategic uncertainty.