Why it matters: A rotating detonation ramjet could raise range or payload in a missile-sized package. It could also cut booster demand if it lights at lower speeds. However, the real test is repeatable performance under flight-like conditions.

Key Facts

- Announced: 14 January 2026 (company statements).[1][2]

- Test site: GE Aerospace Research Center, Niskayuna, New York.[2]

- What they tested: Inlet + combustor in direct-connect runs for ignition and cruise conditions.[1]

- Propulsion concept: Liquid-fuelled rotating detonation combustion in a ramjet architecture, matched to a tactical inlet design.[1]

- Claimed benefits: Higher thrust and efficiency, smaller size/weight, and lower-speed ignition (potentially reducing booster size).[2]

- Next step: Additional technology maturation planned through 2026.[1]

What GE and Lockheed tested—and why it matters for hypersonic missiles

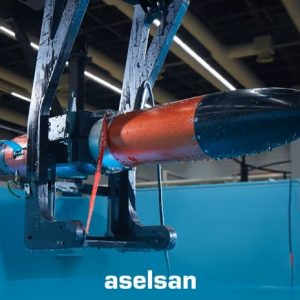

On 14 January 2026, GE Aerospace and Lockheed Martin said they completed a test series for a liquid-fuelled rotating detonation ramjet aimed at hypersonic missile applications.[1][2] The teams ran the work at GE’s Research Center in Niskayuna, New York. They described it as the first technical output under a broader joint technology development arrangement.[1]

In practical terms, air-breathing hypersonic missiles fight a tight triangle. They need compact packaging, efficient combustion, and reliable takeover after boost. Therefore, a smaller and more efficient combustor can change the range–payload trade. It can also free internal volume for fuel or a larger payload.[2]

In addition, GE said the concept could ignite at lower speeds.[2] If that holds in later testing, designers may shrink the booster stage. As a result, the weapon could gain volume and mass margin for mission payloads.

Rotating detonation ramjet: the technical idea, without the hype

Conventional ramjets rely on continuous combustion. By contrast, rotating detonation uses a detonation wave that travels around a chamber. In theory, that cycle can raise pressure and improve efficiency. GE and Lockheed aim to apply that concept inside a missile-sized ramjet package.[1][2]

However, the hard part is control, not ignition. The combustor needs the right airflow, pressure, and temperature at all times. Consequently, inlet design becomes a pacing item. Lockheed said the effort builds on its ramjet inlet experience, while GE supplies the detonation combustion technology.[1]

Moreover, the inlet must condition high-speed airflow without large losses. It must also keep operability margins during altitude changes and manoeuvre. Otherwise, the combustor may lose stability when conditions shift.

Test approach: what “direct-connect” does—and does not—prove

The companies said engineers injected airflow into the inlet to replicate supersonic flight conditions across a range of speeds and altitudes.[1] They also highlighted higher operating altitudes, where thinner air can make stable combustion harder.[1] This focus is a useful signal, because altitude often compresses stability margins.

Direct-connect setups help teams isolate inlet–combustor matching and ignition behaviour. They also support repeatable runs under controlled boundary conditions. Nevertheless, they do not equal a full-up flight demonstration. For example, they typically do not capture all vehicle flow interactions, thermal soak, and guidance-driven transients.

Programme and market context: propulsion maturity as the schedule driver

For many buyers, hypersonics now hinge on repeatable manufacturing and field support. Therefore, compact propulsion systems with better fuel economy carry strategic value. Lockheed framed the outcome as the product of “two years of internal investment,” and stressed “affordable capability” delivered at “the speed of relevance.”[1]

Meanwhile, third-party reporting points to the intended speed bracket. FlightGlobal reported that the concept targets “Mach 5 and beyond,” and it emphasised the compact form factor for missile integration.[3] In addition, the same report notes parallel detonation-related work elsewhere in the US propulsion base, which adds competitive pressure on cost and industrialisation pathways.[3]

Assessment: what would turn this into a real inflection point

This announcement signals technical progress. Still, programme value will depend on whether the architecture delivers predictable performance at flight-representative conditions. Several hurdles usually separate a promising test from deployable hardware:

1) Operability across altitude and speed

The companies called out higher-altitude operation as a challenge area.[1] Next, observers should watch for evidence of stability margin, not just “it ran.”

2) Thermal management and durability

Detonation cycles can impose harsh thermal loads. Therefore, durability, cooling, and materials may become the long pole. This matters even more if the goal is affordable production, not bespoke demonstrators.

3) Inlet–combustor matching under transients

Hypersonic inlets are unforgiving. Small distortions can create large losses. Consequently, the design must tolerate real-world variability, including manoeuvre and atmospheric change.

4) Manufacturability and quality assurance

Even if efficiency improves, acquisition outcomes will follow repeatability. That includes tolerances, inspection, and process control at scale. In short, the industrial system must match the performance claim.

Implications and next milestones to watch in 2026

GE Aerospace and Lockheed Martin said they plan further maturation work throughout 2026.[1] Accordingly, the most decision-relevant indicators will likely include: broader envelopes (mass flow, temperature, and pressure), longer-duration runs, repeatability across conditions, and any transition planning toward integrated flight demonstrations.

Finally, for programme offices and suppliers, the key question is simple. Can this inlet–combustor package improve the cost-per-effect curve for hypersonic weapons while staying manufacturable? If it can, it may influence future design choices across the air-breathing hypersonic portfolio.

Further Reading

- Defence Agenda coverage: hypersonic missiles[4]

- Defence Agenda coverage: propulsion and engines[5]

- Lockheed Martin release (14 January 2026)[1]

- GE Aerospace release (14 January 2026)[2]

- FlightGlobal report (15 January 2026)[3]

References

- Lockheed Martin, “GE Aerospace and Lockheed Martin Demonstrate Rotating Detonation Ramjet for Hypersonic Missiles,” 14 January 2026. Source

- GE Aerospace, “GE Aerospace and Lockheed Martin Demonstrate Rotating Detonation Ramjet for Hypersonic Missiles,” 14 January 2026. Source

- Ryan Finnerty, FlightGlobal, “GE Aerospace and Lockheed Martin test new rotating detonation ramjet for hypersonic weapons,” 15 January 2026. Source

- Defence Agenda internal tag page: Hypersonic missiles. Source

- Defence Agenda internal tag page: Propulsion and engines. Source