Why NATO Multi-Domain Operations Matter

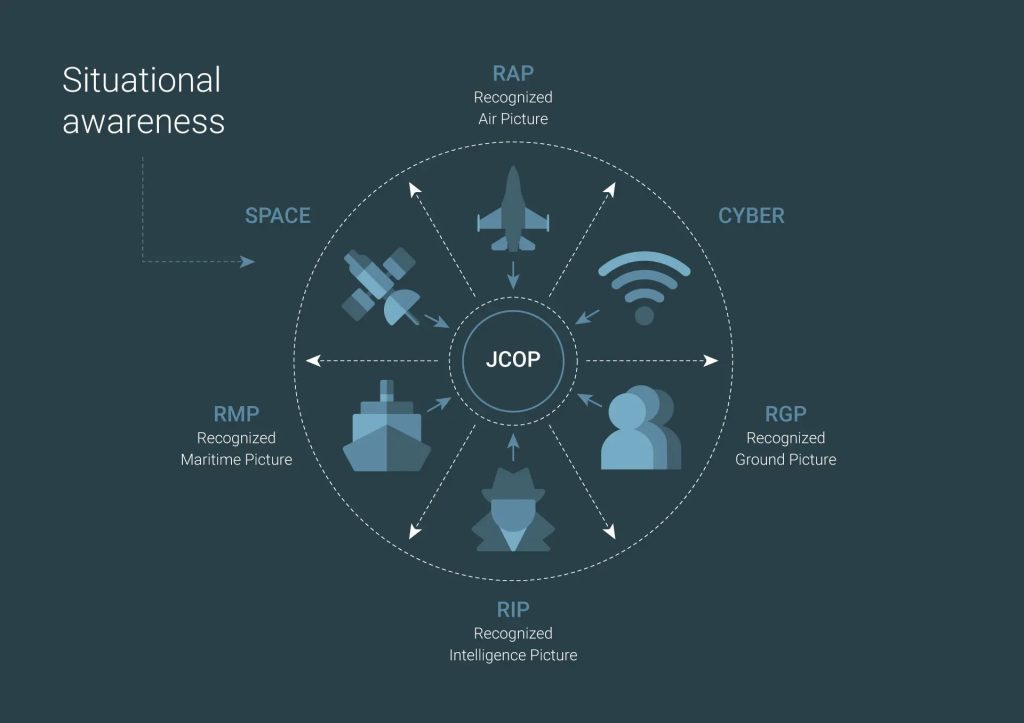

NATO multi-domain operations will shape how the Alliance deters and fights in the coming decade. In future crises, success will depend on how quickly forces can combine effects across land, air, sea, space, cyber and the electromagnetic spectrum. Consequently, the Alliance’s ability to integrate these domains will be a central measure of its credibility.

Today, however, there is still a clear gap between the multi-domain vision and what commanders can actually do. Political and strategic documents describe seamless integration, yet units in the field often work with legacy systems, service silos and slow decision cycles. As a result, the promise of NATO multi-domain operations frequently collides with everyday operational friction.

The Strategy–Reality Gap Inside the Alliance

The gap begins with concepts and language. Most allies endorse the multi-domain idea, but they do not share a single, detailed doctrine for NATO multi-domain operations. Instead, each nation develops its own concepts, networks and data standards. In many cases, these separate tracks do not connect easily, which reduces the speed and coherence of allied responses.

Moreover, institutional culture slows down integration. Service-centric identities still shape planning, procurement and career paths. Therefore, land, air, maritime, cyber and space effects are too often planned in parallel rather than from a unified, multi-domain perspective. Over time, this fragmentation undermines the very agility that multi-domain operations are meant to provide.

Lessons from Ukraine: The Cost of Partial Integration

The war in Ukraine offers a powerful, real-time illustration of both the potential and the limits of multi-domain integration. On the positive side, the combination of ISR, integrated air and missile defence, and long-range fires shows how coordinated, cross-domain effects can change the course of a campaign. For example, timely data from space and airborne sensors can enable rapid, precise strikes against high-value targets.

At the same time, the conflict also reveals the risks of partial integration. Where links between sensors and shooters remain brittle, operations slow down. Where cyber and electronic warfare are not fully aligned with manoeuvre and fires, adversaries gain room to manoeuvre, deceive and disrupt. As a result, every seam between domains becomes a potential vulnerability to exploit.

What Must Change by 2030

By 2030, NATO multi-domain operations must evolve from an ambitious concept into a dependable operational edge. To achieve this, defence leaders need to act in three closely related areas.

Shared Concepts and Doctrine

First, allies should agree on shared multi-domain concepts, planning tools and training standards. With a common playbook, combined forces can plug in faster and operate with more trust. Furthermore, shared doctrine reduces the need to “reinvent” integration in every new operation, saving both time and political capital.

Interoperable, Coalition-Ready C2 Networks

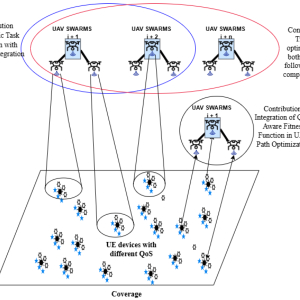

Second, the Alliance must build interoperable and secure C2 networks that are “coalition-ready” from the outset. These networks should connect sensors to shooters through clear data standards, resilient architectures and agreed security frameworks. Over time, AI-supported decision aids can help commanders filter information, prioritise targets and synchronise effects more rapidly. Consequently, decision cycles can shrink from days to minutes.

Leaders Who Think and Act Across Domains

Third, education and training systems need to produce leaders who are comfortable thinking and acting across all domains. This implies earlier exposure to multi-domain problem-solving, not just single-service tasks. In addition, flatter command structures and clearer authorities will help headquarters react under pressure, rather than waiting for long approval chains.

Strategic Choices for Defence Leaders

Delivering on NATO multi-domain operations is not only a technical challenge; it is also a strategic choice. Budgets are limited, so allies must prioritise capabilities that strengthen multi-domain integration instead of narrow, service-specific projects. Otherwise, new investments risk adding complexity without improving overall combat effectiveness.

Cultural reform is equally important. Flatter hierarchies, more joint career paths and routine multi-domain exercises can gradually normalise cross-domain thinking. Meanwhile, closer coordination with industry and technology partners will be essential to align digital, industrial and doctrinal reforms.

Conclusion: A Narrow Window to Act

If NATO gets this right, NATO multi-domain operations will give the Alliance a genuine edge in any high-end conflict. Integrated, resilient and fast-moving multi-domain architectures can deny adversaries the ability to exploit seams and surprise allied forces. Conversely, if the Alliance moves too slowly, the strategy–reality gap will widen and opponents will gain more options to disrupt, deceive and overwhelm.

Ultimately, the 2030 horizon is not just a planning marker; it is a real deadline. Decisions taken in this decade will determine whether NATO multi-domain operations become a routine operational advantage or remain an unrealised aspiration.

For a deeper dive into NATO’s wider deterrence posture and defence industrial base, see our related analysis on NATO deterrence and defence planning.

For further background on emerging concepts for NATO multi-domain operations, you can also review: