Threats to undersea infrastructure now sit at the centre of great power competition. The seabed carries a dense web of submarine data cables, energy pipelines and sensor networks. These systems move most of the world’s data and a large share of its energy. Because of this, they have become attractive targets in the grey zone between peace and open conflict.

Recent sabotage and suspicious incidents show that the deep ocean is no longer a safe place for critical infrastructure. State and state-aligned actors test how far they can go in probing or damaging cables and pipelines without triggering a conventional response. In effect, a new era of “seabed warfare” has begun. Control of the depths now matters as much as control of the air or cyber space.

Recent Incidents: Nord Stream, Balticconnector and the Baltic Sea

In September 2022, powerful explosions ripped apart the Nord Stream gas pipelines in the Baltic Sea. The blasts severed a major energy route between Russia and Europe and highlighted how exposed seabed pipelines are to covert attack. One year later, in October 2023, another shock followed in the same region.

That month, the Balticconnector gas pipeline and parallel telecom cables between Finland and Estonia stopped functioning after damage on the seabed. During the same week, a data cable between Sweden and Estonia also suffered damage. Finnish investigators said the Balticconnector case likely involved sabotage, not an accident. Regional governments suggested a coordinated effort against Europe’s critical infrastructure.

NATO reacted by increasing naval patrols, mine-sweeping and surveillance in the Baltic Sea. Officials warned that these incidents increased concern about the security of energy supplies in Northern Europe. Open-source reporting linked some suspicious activity to specific vessels, including Russian and Chinese-flagged ships. Formal attribution remains politically sensitive, yet the strategic message is clear: undersea infrastructure has become a new front line.

For additional context on hybrid attacks against energy infrastructure, see our related analysis on hybrid warfare against critical infrastructure .

Adversary Capabilities: Russia, China and Seabed Warfare

Russia has built specialised maritime forces for seabed warfare. Its “ghost fleet” includes spy ships, deep-diving submarines and special mission vessels. These platforms locate, tap or cut fibre-optic cables on the ocean floor. NATO assessments state that Moscow focuses heavily on options to damage undersea infrastructure during a crisis.

China is also expanding its undersea toolkit. Chinese survey vessels have mapped cable routes in the Pacific and around Taiwan. Several incidents near Taiwan’s outer islands involved repeated cuts to seabed cables that carried internet traffic. In early 2025, Taiwan detained a Chinese-flagged ship after one such series of breaks. Earlier, in 2023, Chinese vessels had already snapped cables to the Matsu islands.

Chinese activity now reaches beyond the Indo-Pacific. A Chinese vessel appears in some reporting as a possible suspect in the Balticconnector incident. If this pattern continues, Beijing will show that it can apply grey-zone pressure against undersea infrastructure on a global scale, not only near its own shores.

Western states are starting to respond. The UK and France have ordered dedicated undersea surveillance ships to monitor key cables and pipelines. NATO has set up a Cell on Undersea Infrastructure Security to coordinate analysis and protection. Even so, the scale of the task is huge. Roughly 450 active submarine cables carry about 97% of intercontinental data, and seabeds are covered by oil and gas pipelines that are hard to watch continuously.

Why Undersea Infrastructure Is So Vulnerable

Undersea cables and pipelines were never designed to withstand deliberate attack. Most fibre-optic cables are only as thick as a garden hose. Many lie exposed on the seabed, or only lightly buried. In international waters, no state has clear enforcement authority, and physical protection is weak.

When a cable fails, teams must first find the exact location and cause. That process can take days or weeks, especially in deep or stormy seas. A single cut can disrupt internet connectivity, banking and financial transactions, and military C4ISR traffic for entire regions. A ruptured pipeline can cause energy shortages, price spikes and serious environmental damage.

Undersea sensor networks face similar risks. Fixed sonar arrays, seismic sensors and underwater acoustic systems help navies track submarines and monitor ocean activity. An adversary that disables or deceives these sensors gains more freedom of movement for submarines and unmanned underwater vehicles. At the same time, NATO and partners lose vital situational awareness in key chokepoints.

Systemic Interdependencies and Hybrid Warfare

Threats to undersea infrastructure affect far more than naval operations. Modern societies rely on these seabed assets for connectivity and energy. When a cable is cut, banks, stock markets, cloud services and government networks can all feel the impact. In that sense, a single undersea incident can trigger a multidomain crisis.

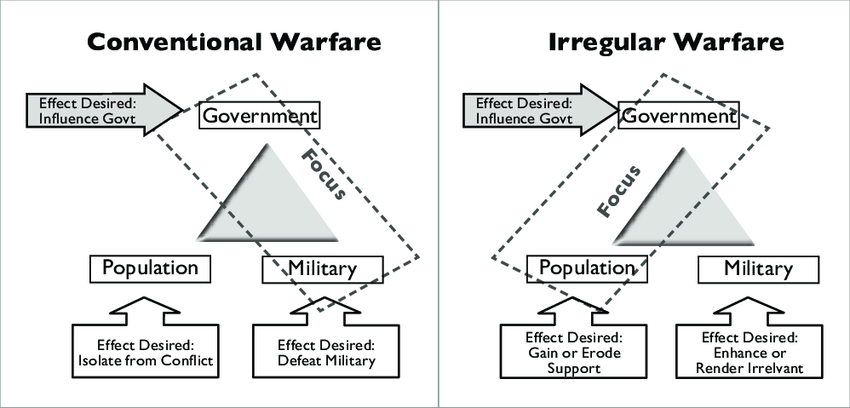

Adversaries can combine physical damage at sea with cyber operations on land networks and information campaigns online. They might cut a cable, hack a data centre and spread rumours about widespread outages at the same time. This hybrid playbook complicates attribution, weakens public trust and makes political decision-making harder.

Alliance networks create additional interdependence. U.S. military communications rely heavily on civilian cables that come ashore in allied countries. A strike against a cable off Norway, the UK or Japan can disrupt Pentagon operations even though it occurs far from U.S. territory. Yet international law still struggles to define protection and enforcement rules for cables and pipelines in international waters. That gap makes a coordinated defence and response more difficult.

For a broader view of how seabed warfare links to deterrence, see our article on seabed warfare and deterrence .

Strategic Implications: Undersea Infrastructure as a Front Line

Strategically, governments now treat undersea infrastructure as a national security issue, not just an engineering concern. In a NATO–Russia crisis, the first hostile move may come as a series of cable or pipeline disruptions, not as visible troop movements. These attacks could slow European decision-making, weaken public communication and erode confidence in governments’ ability to protect basic services.

Deterrence postures therefore need an update. Allies must signal that serious underwater sabotage by a state actor can cross political red lines, even if the attacker hides behind plausible deniability. This does not mean that every unexplained cable fault should trigger escalation. However, repeated and clearly targeted attacks on critical seabed infrastructure cannot be treated as routine technical failures.

Resilience also plays a strategic role. States can diversify routes, add new cables on less exposed paths and increase landing points to avoid single points of failure. Some defence planners also explore quantum-secure satellite links and proliferated LEO constellations as partial backups for essential data. These systems have their own weaknesses but still reduce the reward from attacks on any one layer.

Operational Implications: Monitoring, Hardening and Repair

At the operational level, navies and coast guards must treat key cables and pipelines as critical “terrain”. They need to patrol undersea chokepoints, watch vessel movements closely and use unmanned underwater vehicles for regular inspections. Routine patrols can deter casual tampering and may catch hostile activity early.

Underwater ISR (intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance) will become more important. Towed sonar arrays, fixed sensor lines and AI-based anomaly detection on fibre-optic signals can reveal suspicious patterns in near real time. During crises, naval forces may also need to escort repair ships and deploy assets to protect high-value cable segments and pipeline junctions.

Rapid repair capability forms another key pillar. Governments can pre-position cable-laying and repair ships, stockpile spare cable sections and streamline legal procedures for emergency work. Close cooperation with telecom and energy companies is essential, since they own and operate most of the infrastructure. Regular joint exercises that simulate cable breaks and pipeline damage will improve readiness and coordination.

Hardening measures can reduce risks further. Operators can bury cables deeper in the seabed, use stronger armouring and integrate self-monitoring sensors that detect strain or tampering. These steps raise the cost and complexity of attacks. However, due to cost and scale, states will need to prioritise the most critical routes and nodes for upgrades.

Policy Implications: Rules of the Road and Governance Gaps

Policy-makers must close legal and governance gaps while working with industry and allies. Many experts now call for basic “rules of the road” for behaviour on the seabed. These norms would resemble existing expectations that discourage interference with spacecraft or condemn cyberattacks on civilian power grids.

Possible measures include pledges not to attack cables and pipelines in peacetime and commitments to assist with repairs after accidents. States could also increase transparency around some deep-diving operations to reduce the risk of miscalculation. Adversaries will likely resist full openness, but even partial steps can help.

At home, governments must decide who leads undersea protection and how to fund it. Navies, coast guards or specialised joint commands could take the lead, supported by intelligence agencies. Legal frameworks need to allow secure sharing of sensitive information with cable and pipeline operators when threats arise. Clear mandates and budgets will help avoid gaps in responsibility.

Public communication also matters. An undersea attack can cause confusion and fear if authorities react slowly or inconsistently. Governments should prepare plans to explain outages, provide realistic repair timelines and offer temporary alternatives such as satellite bandwidth for critical services. Strong, credible messaging reduces the psychological payoff of sabotage.

Conclusion: Securing the Seabed by 2030

By 2030, protecting undersea infrastructure will demand the same attention that states once reserved for airspace and cyberspace. Threats to undersea infrastructure now sit at the heart of debates about deterrence, resilience and hybrid warfare. The seabed is no longer a quiet backdrop to global trade. It has become an active arena where covert actions can create global effects.

Meeting this challenge will require better surveillance, stronger public–private partnerships, clearer law and more credible deterrence. It will also require redundancy and rapid repair so that no single strike can cripple a nation’s connectivity or energy supply. The choices allies make today will decide whether the undersea commons remains a shared enabler of prosperity — or stays a major vulnerability in the next era of strategic competition.