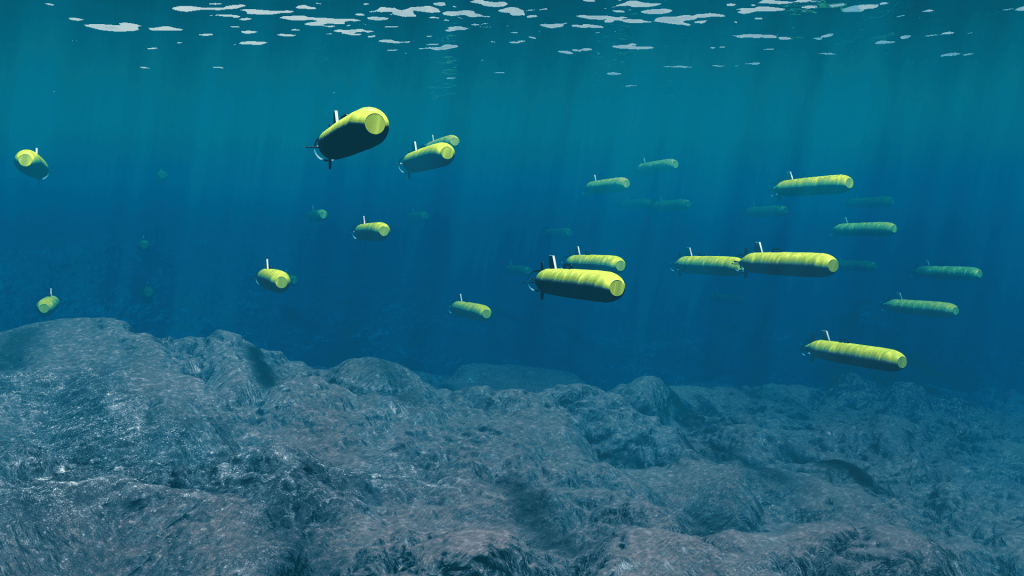

Autonomous underwater systems and swarming drones are changing the character of warfare as much as precision-guided munitions did in past decades. Unmanned vehicles now operate beneath the waves, while swarms of low-cost drones crowd the skies. These technologies promise reach, persistence and mass at lower cost. However, they also introduce serious risks of miscalculation, misattribution and rapid escalation.

Undersea autonomy extends naval power into depths that were once too risky or expensive for routine patrols. At the same time, drone swarms offer a new way to overwhelm defences and threaten high-value platforms. Together, they push military decision-making toward higher speed and greater dependence on AI-enabled systems, raising hard questions about control and accountability.

The Rise of Autonomous Underwater Systems

Navies now field Autonomous Underwater Vehicles (AUVs) in many sizes and roles. Small systems handle reef surveys, mine countermeasures and coastal reconnaissance. Larger platforms act as crewless submarines, able to patrol far from home ports and perform high-risk missions without endangering crews.

Russia’s Poseidon AUV illustrates the strategic end of this spectrum. Official statements describe it as a nuclear-powered, nuclear-armed, long-range undersea vehicle designed to cross oceans autonomously and strike coastal targets. It sits somewhere between a doomsday torpedo and a crewless strategic submarine.

A platform that navigates on its own for thousands of kilometres and delivers a nuclear payload blurs the line between classic nuclear deterrence and lethal autonomy. Even if humans decide when to launch, the image of “roaming nuclear drones” at sea complicates crisis management. Malfunction, misperception or loss of contact could all create scenarios that planners struggle to model.

Other powers are unlikely to stand still. By 2030, China could deploy AUVs to shadow carrier strike groups, guard chokepoints or probe undersea cables. The United States is developing extra-large unmanned submarines such as the Orca programme, with missions ranging from mine-laying and decoy operations to anti-submarine warfare. As these fleets grow, contests at sea will reach deeper and closer to seabed infrastructure, often under a veil of deniability.

For a related discussion of seabed risks, see our article on threats to undersea infrastructure .

The Dawn of Swarming Drones

Above the surface, the era of swarming drones is beginning. A swarm uses large numbers of small unmanned aircraft that coordinate via networking and AI. Operators set broad objectives, while the swarm distributes tasks and adapts to threats in real time.

Conflicts such as the war in Ukraine offer early glimpses. Ukraine has launched multiple explosive drones in coordinated strikes on airfields and naval targets. Russia has sent waves of Iranian-designed Shahed drones to wear down Ukrainian air defences. These examples are crude compared to future designs, yet they show the core logic: massed, cheap platforms can challenge sophisticated defences.

U.S. and allied militaries now treat swarms as a central element in future concepts. Initiatives such as the Pentagon’s “Replicator” plan aim to field thousands of attritable autonomous drones in short timeframes to counter larger adversary fleets. The aim is simple: use “small, smart, many” systems to offset the numerical and cost advantages of large platforms.

A swarm of low-cost drones could harass, confuse or even disable a billion-dollar warship through sheer saturation. However, this comes at a price. As autonomy and scale increase, behaviour becomes harder to predict. Complex swarms operating under fire and electronic attack may respond in ways their designers did not expect, raising the risk of unintended strikes, collateral damage or fratricide.

Regional Levelling Effects

Regionally, autonomous underwater systems and swarming drones act as powerful levellers. States or groups with limited budgets can still threaten sophisticated forces. In the Gulf, Iran experiments with combinations of drone boats, small unmanned aircraft and fast attack craft to challenge naval patrols and commercial shipping.

In the Indo-Pacific, China tests swarms of loitering munitions and unmanned surface vessels designed to encircle or saturate targets. Scenarios in the Taiwan Strait often feature large numbers of drones acting as early-warning tripwires or as first-wave attackers. Conversely, defenders may use their own swarms for ISR and area denial, increasing transparency but also crowding an already tense air and maritime picture.

Along NATO’s flanks, swarms can support surveillance of long borders or contested seas. They could also serve as tools for probing air defences if used by adversaries, creating “drone storms” that test radar coverage and reaction times. Non-state actors add another complication: as components and AI tools become cheaper, terrorist groups could build improvised swarms from hobby drones to strike infrastructure or public events.

Systemic Interdependencies: Autonomy, AI and Escalation

Autonomy in warfare links closely to AI ethics, command and control, and escalation management. The more militaries delegate to autonomous systems, the more they depend on robust communications, navigation and data networks. A breakdown in those links can turn a useful asset into an uncontrolled liability.

Swarms and AUVs also stress traditional early-warning systems. A dense swarm may appear on radar as a confusing cloud of returns. Quiet electric undersea drones can slip under sonar coverage or hide in traffic around commercial shipping. As a result, decision loops must speed up, and commanders may lean more on AI to classify and respond to threats.

Electronic warfare is woven through this picture. Swarms rely on networking, so jamming, spoofing or hacking their links becomes a key defensive tactic. Undersea drones depend on acoustic communication and occasional links to satellites or surface buoys; adversaries will try to disrupt these channels. Designers, in turn, seek ways to make autonomy robust against interference, creating an ongoing contest between offence and defence.

Legal frameworks lag behind. Debates under the Convention on Certain Conventional Weapons (CCW) about “lethal autonomous weapons” have not yet produced binding rules. Yet by 2030, AI-enabled systems may make life-and-death decisions in milliseconds in some scenarios. Without clearer norms, states risk sliding into a world where machines drive escalation faster than humans can react.

For a broader look at autonomy, nuclear stability and escalation, see our analysis on AI in nuclear command and control .

Strategic Implications for Deterrence

Strategically, autonomous underwater systems and swarming drones challenge traditional deterrence concepts. Massed, low-cost drones allow smaller actors to threaten capital ships, fixed bases and high-value assets. This undercuts long-held assumptions about the protection that scale and sophistication provide.

Major powers must rethink force design. Navies may increase emphasis on distributed maritime operations with more, smaller platforms and larger unmanned components. Land forces may disperse command posts and logistics nodes to avoid becoming lucrative swarm targets. The goal is to reduce the payoff from any single successful attack.

There is also an arms-control dimension. Nuclear-armed autonomous systems like long-range undersea vehicles carry outsized escalation risks. Confidence-building steps could include commitments not to deploy nuclear warheads on autonomous delivery platforms, and to keep humans firmly in the decision loop for any nuclear use. Even if a comprehensive ban on “killer robots” remains unlikely, narrower limits on particularly destabilising applications may be achievable.

Operational Implications: Tactics, Training and Countermeasures

Operationally, forces must learn both to employ and to counter autonomy. On the offensive side, commanders will task swarms and AUV flotillas with mission-level orders rather than micro-managing individual drones. This demands new command-and-control concepts, extensive simulation and clear fail-safes if communications fail.

On the defensive side, counter-swarm and counter-AUV capabilities become essential. Ships and bases will need layered defences that blend electronic warfare, cyber effects, high-energy weapons and kinetic interceptors. Sensors and fire-control systems must handle many small, fast targets at once, not just a few large missiles or aircraft.

At sea, anti-submarine warfare will expand into anti-AUV warfare. Surface vessels, submarines and maritime patrol aircraft will require sensors tuned to detect small, quiet underwater vehicles. Navies may deploy their own hunter-killer AUVs to track or neutralise adversary drones near critical infrastructure or high-value units.

Training must keep pace. Exercises should include scenarios where one side fields large swarms or “wolf-pack” UUVs, forcing the other to adapt in real time. These drills reveal gaps in doctrine and integration long before a real crisis, when the cost of learning would be far higher.

Policy Choices: Keeping Humans in Control

Policy-makers have a limited window to shape norms before practice solidifies. A practical starting point is to focus on meaningful human control. Many states already endorse the principle that humans should retain authority over life-and-death decisions, even when using AI-enabled systems.

National policies can codify this. Defence ministries might prohibit deployment of fully autonomous strike systems that lack a human override, or ban autonomous nuclear delivery vehicles outright. They also need detailed rules of engagement for AI-controlled systems that define when automatic responses are acceptable and when human approval is mandatory.

Internationally, crisis-management tools must evolve. If an autonomous system contributes to a serious incident — for example, a swarm misidentifies a target — adversaries will need channels to clarify intent and de-escalate. Existing hotlines could be adapted to handle “AI incidents” alongside more traditional accidents at sea or in the air.

Finally, autonomy brings a human-capital challenge. Armed forces require more personnel who understand AI, robotics, software and data. Policies that support recruitment, specialist training and exchanges with industry and academia will help militaries integrate autonomy in a controlled and informed way.

Conclusion: Governing Autonomy Before It Governs Us

Autonomous underwater systems and swarming drones will become more capable, more numerous and more central to military planning over the next decade. They can extend reach, reduce risk to personnel and impose new costs on adversaries. Yet without careful design and clear rules, they can also accelerate escalation and erode human control over war.

The challenge for policy-makers and commanders is to harness these tools without letting them dictate the pace and terms of conflict. If they can keep humans firmly in the loop, invest in robust countermeasures and update doctrine and law together, autonomy can strengthen deterrence. If they cannot, future crises may be shaped by “flash wars” at machine speed, with consequences that no leader intended.